Keeping Tabs on your Tabs | Why You Need a Tab Day

Distracted from distraction by distraction. —T.S. Eliot

The real problem of humanity is the following: We have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions and godlike technology. And it is terrifically dangerous, and it is now approaching a point of crisis overall. ―Edward O. Wilson

I will cut adrift—I will sit on pavements and drink coffee—I will dream; I will take my mind out of its iron cage and let it swim. —Virginia Woolf

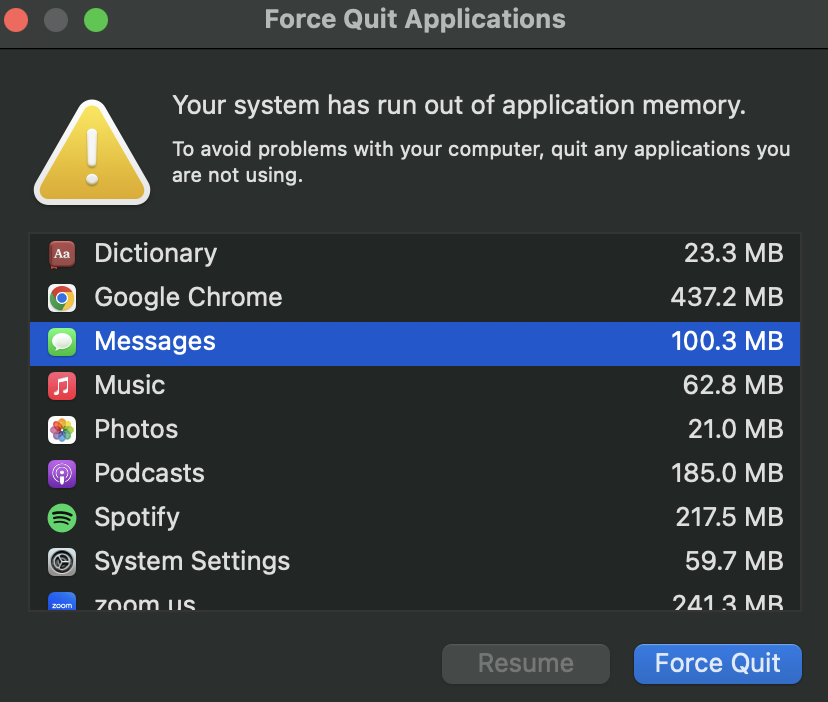

Above: A tsunami of tabs accumulated while surfing the web.

If you're anything like me, you are reading this very sentence surrounded by a digital forest of open browser tabs spread across your iPhone, iPad, and laptop. Your computer fan is going a mile a minute, whirring wildly in order to cool overworked CPUs that are drowning in the digital deluge of human knowledge.

As I peck away at this piece, my disheveled desktop currently has seven browser windows open with an average of nine tabs each. Rather ironically, not only has my Chrome browser crashed twice, but this pernicious popup keeps rearing its ugly head:

The above is an apt microcosm of modernity.

To be online is to have a debilitating addiction to information by way of browser tabs. The metaphors write themselves.

Tabs are like weeds. They sprout everywhere, and no matter how many you kill, they just keep coming back. As such, they must be kept in check and tended to often.

Managing your tabs is like consuming alcohol. A few drinks is fine. Wonderful, even. Excess is where the real trouble begins. As is said, “everything in moderation.” Whether information or alcohol, you can, in fact, have too much of a good thing.

Tabs resemble the Lernaean Hydra, close one and two or three more sprout up in its place. It's the digital equivalent of a mythological monster that grows back faster, stronger, further no matter how hard you swing your sword cursor or plunge your spear keyboard.

Though there has never been a better time to be alive for a curious person chock full of agency and ambition, our brains need a break. Insatiable inquiry coupled with infinite access to everything humanity has ever done, asked, or achieved is a dangerous combination.

Something has got to give. We are writing checks with our curiosity that our brains simply cannot cash.

As I wrote in Stop Tweeting, Start Thinking:

In many ways, we are all slaves to silicon and semiconductors; to those devices that ping, bing, and buzz at all hours of the day and night.

Hooked on an intermittent dopamine drip of ephemeral news cycles, Cancel Culture casualties, and infinite scrolling, we live in what my friend David Perell has aptly termed the Never-Ending Now.

The constant connectivity of the Never-Ending Now undermines our ability to learn from the enduring lessons of the past. Without these, we face an unknown future neither equipped nor prepared. We resemble chefs without ingredients, skippers without vessels, carpenters without lumber.

Because of this collective simultaneity, I fear that we are fast approaching the world George Orwell forewarned of in 1984:

Every record has been destroyed or falsified, every book rewritten, every picture has been repainted, every statue and street building has been renamed, every date has been altered. And the process is continuing day by day and minute by minute. History has stopped. Nothing exists except an endless present in which the Party is always right.

When I mentioned this to a close friend of mine, she shared a sage quote with me. It aptly summarizes my thoughts on the Information Age:

We are drowning in information while starving for wisdom. The world henceforth will be run by synthesizers, people able to put together the right information at the right time, think critically about it, and make important choices wisely.

— E. O. Wilson

To visualize this mammoth deluge of data, this inundation of information, look no further than the below infographic:

The above begs a few questions:

How is any sane individual able to keep up?

How do I separate the precious digital wheat from the copious amounts of pixelated chaff?

Is it possible to divine signal amidst this cacophony of noise?

How am I “able to put together the right information at the right time, think critically about it, and make important choices wisely”?

Simply put, how do I keep from drowning?

The amount of information consumed daily now is roughly equivalent to what an extremely educated individual would process in a lifetime 500 years ago.

Visualized, this torrid stream of information might look something like this:

I once read that social media is like being thirsty in the ocean. You look around and all you see is “water” but it’s salt water. The more you drink, the faster you die of dehydration.

To extend the aquatic metaphors, author of The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains Nicholas Carr wrote, “What the [internet] seems to be doing is chipping away my capacity for concentration and contemplation. Whether I’m online or not, my mind now expects to take in information the way the [internet] distributes it: in a swiftly moving stream of particles. Once I was a scuba diver in the sea of words. Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.”

Instead of salt water, science says that our overexposure to digital detritus is slowly killing us. The research is clear that when our physical or digital space is a mess, so too are we:

In 2022, the American Psychological Association warned that growing numbers of Americans were suffering from what one therapist termed “media saturation overload” — a specialized sort of stress that results from encountering a steady, ceaseless “drumbeat” of news.

Research has linked clean, organized spaces — and even just the act of cleaning — to reduced anxiety and fatigue, as well as improved concentration and mood.

Scientists at the Princeton University Neuroscience Institute have used fMRI and other approaches to show that our brains like order, and that constant visual reminders of disorganization drain our cognitive resources and reduce our ability to focus. They also found that when participants cleared clutter from their work environment, they were better able to focus and process information, and their productivity increased.

A study on the effects of clutter in the home found that individuals who felt overwhelmed by the amount of “stuff” in their homes were more likely to procrastinate. Other research has shown that a cluttered home environment triggers coping and avoidance strategies involving snacking on junk and watching TV. While we don’t know if this generalizes to the workplace, it’s possible that cluttered offices may produce employees who make poor eating choices during breaks and spend less time actually working.

Clutter can also affect our general mental health, making us feel stressed, anxious, or depressed. Research from the United States in 2009, for instance, found the levels of the stress hormone cortisol were higher in mothers whose home environment was cluttered; elevated cortisol levels sustained over time can lead to anxiety and depression. (Interestingly, it might work the other way, too. Researchers in the U.S. examined the interplay between stress and workplace clutter and found that stress and emotional exhaustion causes workers to delay making decisions and to keep more material for all their ongoing tasks within easy reach: hence leading to messy workspaces.)

Cleanliness is next to godliness. When you clear the clutter—both physical and digital—your productivity increases.

But how?

Like most things in life, you likely already know what you have to do. You just lack the empty space to let the answer percolate and then crystallize into concrete action.

Nevertheless, below is a simple strategy that has worked well for me.

I write this note on a Tuesday. Or, in my world, Tab Day.

Tab Day is my midweek reset/refresh that falls after Monday's mania and before the midweek malaise. Think of it as a productive speed bump—a pit stop on the information superhighway that forces you to slow down and ask: Do I really need to keep all of...this?

It is as simple as it is effective.

It is a weekly spring cleaning for that place—online— where we increasingly and sadly spend most of our waking—if not working—hours.

It is proactive as opposed to reactive, acting intentionally as opposed to compulsively.

It is one step backward so that you can take many more forward.

The rules are wonderfully simple:

Set aside 60 minutes one day a week

Open all your browser windows

Give each tab a ruthless assessment

Close what doesn't serve you

Read or act on what matters

Bookmark anything genuinely worth revisiting

You're not catching up. You're curating.

You're not consuming everything. You're choosing what matters.

It is not so much a detox as it is a defragmentation.1

It's about putting a dent in the digital deluge.

During this hour, every closed tab triggers the same dopamine hit as checking something off a to-do list. It's not about how many tabs you close, but the act of doing so. Think of it like Marie Kondo for your digital life—holding each tab and then either acting on or disposing of it.

That's it.

It represents a reprieve that allows you to catch your breath in a never-ending race.

It is a reshuffling of the attentional hard drive to ensure you’re being intentional with your time, your attention, and your literal and mental RAM.

What Mortimer J. Adler said about books is pertinent to information writ large: “In the case of good books, the point is not to see how many of them you can get through, but rather how many can get through to you."

We have a scarcity of time and an abundance of information. As Naval Ravikant sagely quipped, “The modern devil is cheap dopamine.” Those endless tabs are just a form of digital methadone, keeping you addicted to the next hit of information.

If you don't manage your tabs, your tabs will manage you. It is the equivalent of the tail wagging the dog, a reactive approach to life versus a proactive one. The less brain capacity cluttered by your tabs, more brain capacity you have to devote to your unique zone of genius.

You don't need more time; you need more focus. Our attention, not the clock, ultimately limits what we can achieve.

In my part of the world, spring has almost sprung.

With April showers and May flowers comes a necessary evil: spring cleaning.

Spring cleaning has ancient roots. You see references to the practice pop up in Judaism and Catholicism, as well as around the Persian and Thai new year celebrations.

Embrace Tab Day as a form of digital spring cleaning.

Close a tab. Open your mind.

The internet will still be there tomorrow.