Getting Down in the Dirt

The soil is the great connector of lives, the source and destination of all. It is the healer and restorer and resurrector, by which disease passes into health, age into youth, death into life. Without proper care for it we can have no community, because without proper care for it we can have no life. ―Wendell Berry

Above: With good soil, ample sunshine, enough water, and helping hands, any plant can grow tall and strong.

Found in each of the synoptic Gospels, the Parable of the Sower is one of the more popular stories in the Bible.

The version related in the Gospel of Luke (Luke 8:4-8) goes as follows:

While a large crowd was gathering and people were coming to Jesus from town after town, he told this parable: “A farmer went out to sow his seed. As he was scattering the seed, some fell along the path; it was trampled on, and the birds ate it up. Some fell on rocky ground, and when it came up, the plants withered because they had no moisture. Other seed fell among thorns, which grew up with it and choked the plants. Still other seed fell on good soil. It came up and yielded a crop, a hundred times more than was sown.”

The story is simple, but its message is sublime.

Like any good fable, the Parable of the Sower applies not only to faith, but also myriad other facets of life. This includes venture capital.

Aside from the obvious (e.g. the earliest venture financing rounds are literally referred to as pre-seed and seed, respectively), the parable is powerful because of how it upends things.

Put simply: most investors focus on the seed. Few direct their attention to the dirt.

Digging deeper (pun very much intended), regardless of how good the seed (company, team, etc), it will choke without the proper soil (market, distribution, etc). In this way, solutions in search of problems resemble seeds in search of fertile ground and so on; the metaphors write themselves. In fact, my friend Paige Finn Doherty did a good job in her aptly-named book From Seed to Harvest.

In the spirit of this radical inversion, investors ought to get dirty by tilling the soil and providing the right nutrients; it’s not about better seeds, but richer soil. By doing so, they increase their surface area for serendipity and success. To use another useful metaphor, this approach resembles a lopsided game of darts: it’s much easier and effective to win by making the dartboard larger instead of trying to hit an already-tiny bullseye.

A larger board means more scoring. More scoring increases the likelihood of victory.

In the numbers game that dictates when VCs hit, they must hit big, playing in the dirt leads to a bounteous harvest for founders, funders, and employees alike.

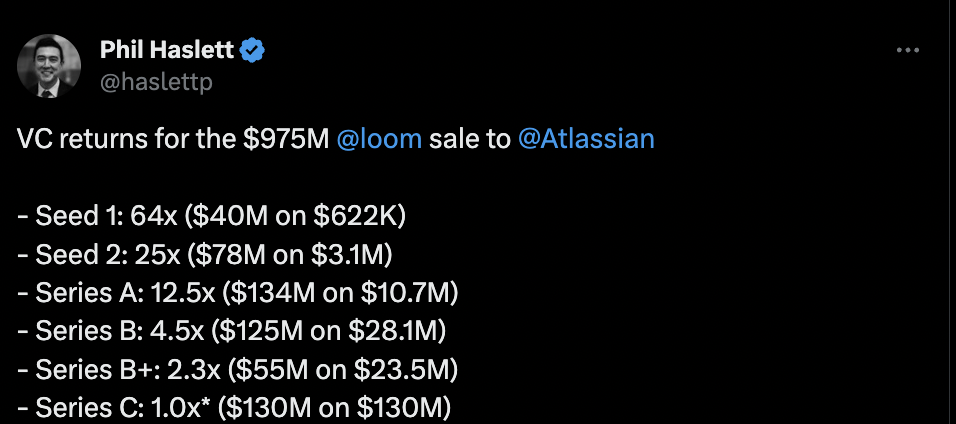

Just as competitors race to the bottom on price—VCs race to the beginning on stage. This is logical—it’s better to have a higher percentage of a lower valuation—but risky. That said, with greater risk comes greater reward given how markets have been acting as of late:

Figma

Loom

Instacart

Per the above, it’s easier to sleep at night the earlier you invest.

How can investors make these earlier, better bets?

Concentrated composting via sceniuses made up of the right people with the right skills in the right place working on the right ideas. Such a combination is all but guaranteed to lead to the leaping emergent effects that produce the great companies of tomorrow.

Programs such as Sequoia Arc and Greylock Edge are beginning to emerge, but few are as well-structured as Slow Ventures’ PhD.

Founding a company is a hyper concentrated investment in an extremely volatile asset and we want to help founders become better investors of their time. Founders should act with care and diligence, borrow from the best, and do everything they can to 1) understand their odds and 2) tilt the odds in their favor.

This is doubly true for founders with high opportunity cost: mid-career folks and executives who can pull down lots of cash and equity by staying put (and who probably have families to think of). The challenge for those people isn’t getting a business funded but rather finding the business worthy of funding with their time.

We believe that the best way to improve the odds and understand risk/reward is to borrow from academic PhD programs. We work with people who have demonstrable subject matter or domain expertise (people who have earned their “masters degree”) in a subject and give them time on campus, acting as an academic advisor. We want to help entrepreneurs determine if their ideas are 1) novel 2) correct and 3) important before getting to “work in the lab” because at that point they’re locked in and the race has begun.

What does this mean practically?

Only admit candidates in fields in which they have demonstrated serious depth and breadth (a “masters degree”).

Give them the time / space / resources / mentorship to explore the subject, find out where things are headed, what’s been done and what is truly novel.

Only commit to the work once 1) it’s clear what the steps are to proving / disproving the hypotheses and 2) proving / disproving them requires capital.

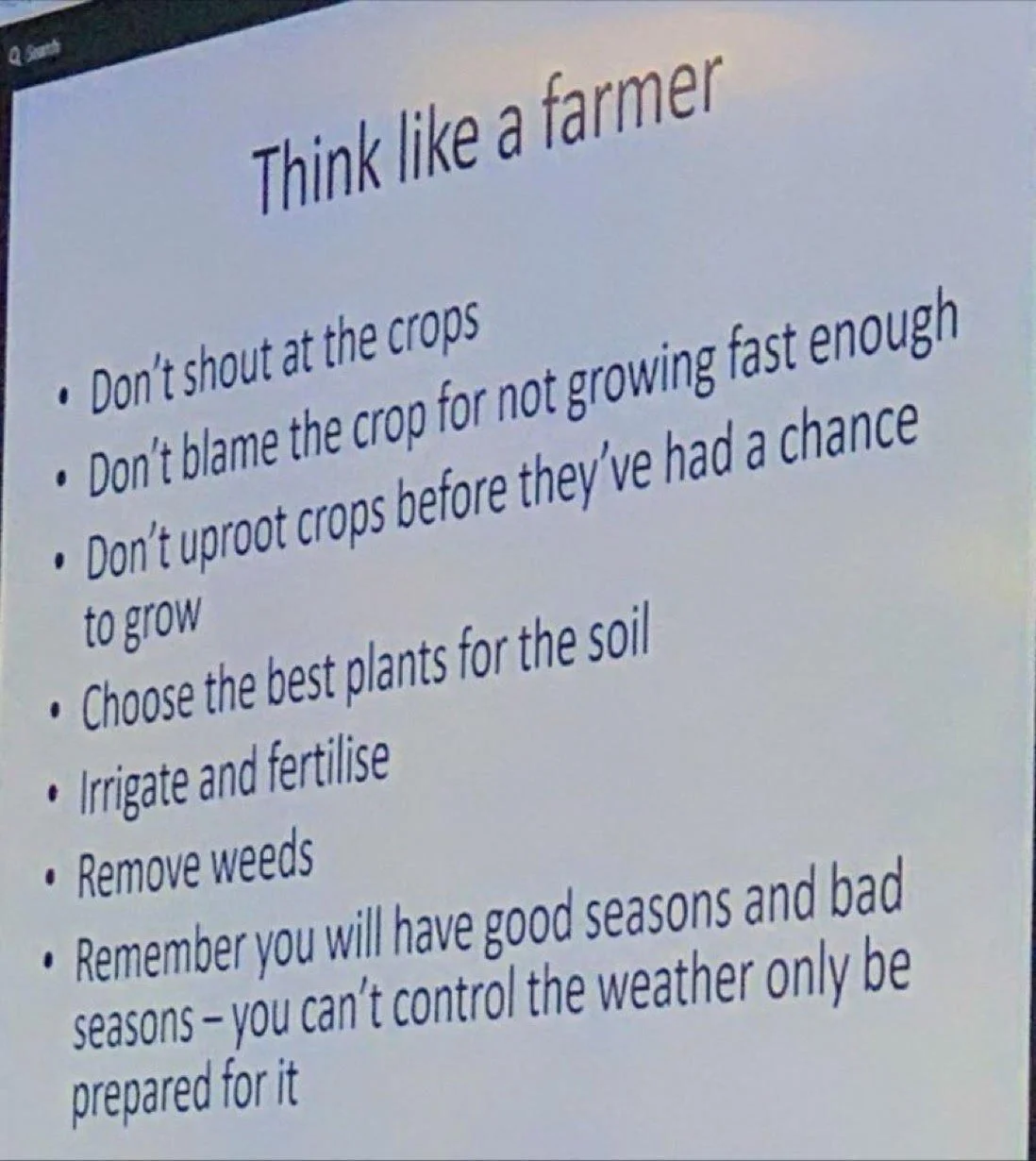

In time, let’s hope more investors follow Slow’s example and get their hands dirty—going from this:

To this:

Through much more of this: