Mortality and Memory

Death be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadfull, for, thou art not soe,

For, those, whom thou think'st, thou dost overthrow,

Die not, poore death, nor yet canst thou kill mee.

From rest and sleepe, which but thy pictures bee,

Much pleasure, then from thee, much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee doe goe,

Rest of their bones, and souls deliverie.

Thou art slave to Fate, Chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poyson, warre, and sicknesse dwell,

And poppie, or charmes can make us sleepe as well,

And better than thy stroake; why swell'st thou then?

One short sleepe past, wee wake eternally,

And death shall be no more; death, thou shalt die.—John Donne, "Holy Sonnet X"

We are to regard existence as a raid or great adventure; it is to be judged, therefore, not by what calamities it encounters, but by what flag it follows and what high town it assaults. The most dangerous thing in the world is to be alive; one is always in danger of one's life. But anyone who shrinks from this is a traitor to the great scheme and experiment of being. The pessimist of the ordinary type, the pessimist who thinks he would be better dead, is blasted with the crime of Iscariot. Spiritually speaking, we should be justified in punishing him with death. Only, out of polite deference to his own philosophy, we punish him with life.

—G.K. Chesterton, “What is Right With the World"

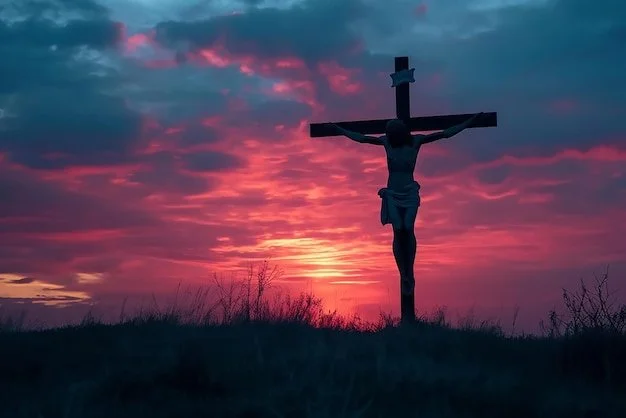

Above: Still-Life with a Skull, Philippe de Champagne, c. 1671

I was fifteen when I first saw a corpse.

Its smell, its sound, and its sight are each indelibly seared into my memory. These vivid details all come rushing back when a wayward comment or loose recollection jostles it loose from my mind’s deep recesses.

Memory is funny like that — it’s a sort of neurological time travel. One small, insignificant hook can yank us from past to present, terrific time to terrible trauma in mere milliseconds…

But that’s another post entirely.

I mention all this as preamble because the death of Queen Elizabeth II has me mediating on mortality, impermanence, and remembrance. Few people are as well-known as she in the modern world. She was, is, and will likely be a modern-day Julius Caesar in terms of fame and notoriety.

The characteristics of her reign are staggering. The UK’s longest-serving monarch, she ruled for seventy years—roughly 30% of U.S. History—met thirteen sitting US Presidents, and visited five Popes.

Indeed, the slice of history through which she lived and the vantage point from which she saw it are both dizzying and awe-inspiring.

And yet, as the famous Italian proverb goes, “after the game, the [queen] and the pawn go into the same box.”

I mean no disrespect or callousness; this is a simple fact about which I often think. After all, no one gets out of this life alive.

Longtime readers will know that Stoicism resonates very deeply with me. One of this solemn philosophy’s core tenets is Memento Mori—Remember that you must die.

Both Marcus Aurelius and Michel de Montaigne—the former reared by Stoicism and the latter influenced by it—frequently examined death. Respectively they wrote:

Don't look down on death, but welcome it. It too is one of the things required by nature. Like youth and old age. Like growth and maturity. Like a new set of teeth, a beard, the first gray hair. Like sex and pregnancy and childbirth...This is how a thoughtful person should await death: not with indifference, not with impatience, not with disdain, but simply viewing it as one of the things that happens to us.

[L]et us deprive death of its strangeness; let us frequent it; let us get used to it; let us have nothing more often in mind than death. At every instant, let us invoke it in our imagination under all its aspects...To practise death is to practise freedom. A man who has learned how to die has unlearned how to be a slave.

Death’s close cousins are impermanence and remembrance. I leave you with two thoughts about these dour relatives as I continue my meditation down the metaphysical rabbit hole of mortality.

Ozymandias by Percy Bysshe Shelley

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Three Deaths

I once read an idea that people die three times:

When their body stops working

When they’re buried

When someone says their name for the last time

Per number three, I share the eulogy that I delivered at my grandfather John T. Landers’ funeral over ten years ago.

Not today, Pop.