Confessions of a Nostalgia Junkie

Imagining the future is a kind of nostalgia. —John Green

People wish to learn to swim and at the same time to keep one foot on the ground. ―Marcel Proust

There is no word for feeling nostalgic about the future, but that's what…tears often are, a nostalgia for something that has not yet occurred. They are the pain of hope, the helplessness of hope, and finally, the surrender to hope. —Michael Ian Black

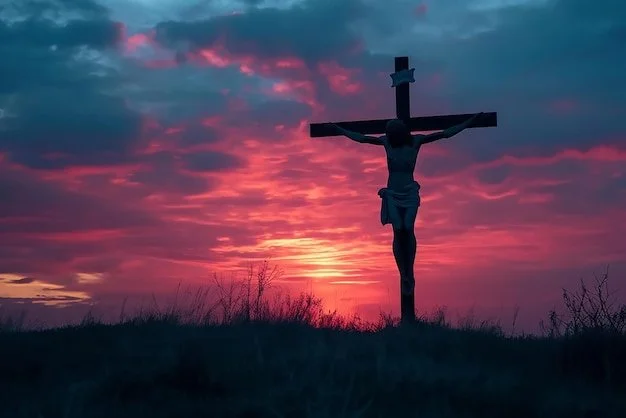

Above: Nostalgia is old and past. Future is young and new. What happens when they become one and the same?

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Janus is celebrated as the god of beginnings, transitions, time, duality, doorways, and endings.

Given his intermediate nature, he is usually depicted as having two faces—each peering (or leering, depending on how you see it) its own, discrete way.

I mention this Roman deity because his visage(s) came to mind when my friend Wesley Braden said that my recent haiku was “an interesting take on the danger of nostalgia.” Curious cat that I am, I called him to learn what he meant.

When Wes shared that he was working on a piece about the perils of a life oriented around nostalgia, I insisted that he allow me to feature it in White Noise.

Like Janus, nostalgia is bidirectional: it can be directed ahead towards an aspirational future or backwards towards a comforting past.

It’s a whipsaw of sorts, a tool that can help or harm depending on what it cuts.

Longtime readers will note that this is not the first time I have featured Wes in White Noise. This will be the third time that his words have graced your respective screens.

He first penned a beautiful, devastating piece on his life with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder:

None of Us Are Whole

He then explored how we consume information and it consumes us in turn:

All the Things We Cannot See: The Rise of the Information Nexus

Wes’ ability to attack complex problems with finesse and grace is a testament to his intellectual firepower, deep curiosity, and penchant for seeking out capital-T truth.

As I previously wrote:

In Wes, I see a lot of myself (or, at least who I aspire to be). He is a man of genuine kindness, deep curiosity, and infectious positivity; the type of friend you smile with on the brightest of days and rue alongside on the darkest of nights…

His special gift for sniffing out the what and the why at the intersection of technology and culture—two things that seem to be converging ever more rapidly in recent years—led to the following piece.

Without further ado, our words:

I love nostalgia.

I crave it.

I seek it out as much as I can.

Through it, I can tap into those choice moments that have made my life beautiful; memories that include the first time I set eyes on my future wife, the thrill of hurling my mortarboard skyward after graduating, the pleasure of curling up with a good novel on a cold winter’s night.

It has a magnetic effect on me; as soon as I teeter up to nostalgia’s edge, its inexorable field grabs me and won’t let go until I am fully sucked in.

Sometimes nostalgia creeps up on me just like a third or fourth beer does, I get a light buzz in my head that becomes a warm numbness as it seeps throughout my body.

Other times I feel a jolt of acuity, of deep and excited focus, that resembles the hour after downing a triple-shot espresso. My heart quickens a bit, my skin flushes, and both today and tomorrow hold more promise than they did just moments before. The past (or, at least, a specific memory of the past) transforms the future. To paraphrase Yogi Berra, it's like déjà vu all over again.

Nostalgia is an almost-perfect drug—it doesn’t bring a hangover, heart palpitations, or an increased risk of cancer. It is a brilliant blend of numbing sedation and stimulating invigoration. It’s almost flawless but, like any drug, it has its risks.

Nostalgia’s risks are nearly as dangerous as those of lung or liver cancer and, similarly, they metastasize inside, blend in with their environment, and thus prove difficult to detect.

Take the example of Vietnam prisoner of war James Stockdale, who endured over seven years at the notorious Hanoi Hilton. When asked which prisoners didn't make it out of Vietnam, Stockdale replied (emphasis mine):

Oh, that's easy, the optimists. Oh, they were the ones who said, 'We're going to be out by Christmas.' And Christmas would come, and Christmas would go. Then they'd say, 'We're going to be out by Easter.' And Easter would come, and Easter would go. And then Thanksgiving, and then it would be Christmas again. And they died of a broken heart. This is a very important lesson. You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end—which you can never afford to lose—with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.

Nostalgia's Purpose

I believe that nostalgia is an evolutionary function designed to help humans survive longer. During and after an encounter with nostalgia, the present and future seem more tolerable, more exciting, more pregnant with possibility.

Picture yourself as a serf in 13th-century Britain.

You’ve lost family to pneumonia, gout, war, plague, farming accidents, and so on.

You pay most of your hard-earned agricultural yield to a baron that you hate.

Your body is chronically sore and battered from a lifetime of physical labor.

The weather is gray, wet, and cold.

In short, you feel miserable most of the time.

And yet, when you look back to your childhood to balmy visions of sitting and telling stories with your parents beside a fire or eating an orange on Christmas, you feel warm and energized.

You believe that the future might just be better than the present.

Nostalgia exists because it helps humans get through difficult seasons—even if those difficult seasons are much longer than the length of the memories. It is so powerful that even a tiny bit of nostalgia is enough to offset decades of malaise, boredom, or agony.

A New Type of Nostalgia

Many think of nostalgia as a one-way street leading to the past because that’s how we have tapped into it. More, it’s the word’s very definition and connotation.

Yet nostalgia can exist for the future just as for the past.

Even if we don’t call it nostalgia, we’re all somewhat familiar with this feeling. If we broaden the definition of nostalgia to be a romanticized and idyllic version of some chapter of a life, we can use the term to cover what follows.

Nostalgia for the future is much more than just daydreaming or visualizing a more grandiose, pleasant, or stimulating future. Instead, just like how it functions for the past, nostalgia for the future is a deep, rich, mental and soulful longing for what can be. In this ordering of the world, the present is just a temporary blip (perhaps good, perhaps bad, perhaps ugly) between sweet memories of the past and pleasant imaginings of the future.

Nostalgia for the future is not spending a lunch break thinking that a trip to Paris might cure the apathy that comes from your work as a CPA.

Nostalgia for the future is filling your sad, cramped cubicle with French phrase books, placing a countdown clock at your desk, staying put in a dead-end job, hearing but not heeding the advice of friends and family to try another career.

Nostalgia for the future subverts the present by prioritizing an idyllic, imagined future. In this way, those that indulge in it make the oldest mistake in the book: they forget that present and future you are one and the same—with scars, warts, and all—sans deliberate change.

The Danger of Nostalgia for the Future

This is precisely where the punch is spiked and things become dangerous: nostalgia for the future leaves us open to devastating disappointment much more than nostalgia for the past does.

Here is how this cycle works in my life:

I nostalgically long for some ideal future state.

This deep, robust desire functions as a crutch that gets me through a difficult season or two. (Or, at least allows me to add a little bit more joy and satisfaction to a season of life in which I’m not fulfilled).

I long for a better, nonexistent future while sleepwalking through a miserable, real present. In this way, I hijack and delude and reorder the present in the image of an imaginary, unobtainable future that has never existed and will never exist. This sort of magical, delusional thinking (let alone action) has never served me (or anyone else well).

Oftentimes my nostalgic longings are so grandiose that I fail to achieve them. But, occasionally I accomplish a bit of what my nostalgia envisaged. And, always, because of how nostalgia romanticizes, reality is much less inspiring or fulfilling than my vision of it.

In the difference between aspiration and actuality lies the danger. This disappointment can give rise to discouragement or even depression.

Functionally, I treat my nostalgic future as an asset and I borrow present joy against it.

Put simply, I tap into the equity of the idyllic future to get an income stream of joy/excitement in the present.

This is fine from a balance sheet perspective because the stream of joy is guaranteed by the asset of my future state.

But what happens when I get to the future and it’s less interesting or fulfilling or exciting than I expected it to be?

My mortgage is underwater.

A mortgage is secured against a home’s value. Even if the borrower can no longer service their monthly loan payment, the bank can repossess the house, sell it, and make their money. Since houses are steady assets that maintain or grow their value over time, this works out well.

However, sometimes houses lose value. In 2008, the overinflated housing market crashed, causing millions of houses to dramatically shed their valuations. Millions of people were left paying off a mortgage that was worth more than their house.

That’s the danger of nostalgia for the future: borrowing against an inflated asset and getting caught paying off a loan that’s bigger than the asset is worth.

In my life, that bill comes due via a nasty mix of anxiety, malaise, and depression.

First, I’m anxious that the actual thing I’m experiencing is quite different from the future for which I nostalgically longed.

Then, as my new reality sets in, I lose motivation to fully imbibe and experience the situation in front of me. Sometimes I even begin to borrow from another idealized future, setting the cycle in motion once more.

Finally, I settle into a depressed state.

In my strongest times, I’m able to recognize the pattern and become present in my current situation, enjoying it for what it is.

In my weakest times, as I admitted above, I fire up the cycle once more by choosing a new future to be nostalgic for.

Though every human is tempted by nostalgia for the future, I think that I am particularly prone to it. I remember my parents telling me as a kid that I needed to enjoy the present and stop longing for “the next fun thing.” Even while enjoying something, I was longing after (and talking about) the next thing I could crave and experience.

To be perfectly honest, I’m nostalgic for the future so often that I cannot produce a concrete example from my life.

I’ve tried to become better at catching myself, but I often find myself being nostalgic—or even taking out debt against the future—and choosing to continue along its alluring path. It’s likely just part of my personality, though perhaps some level of nostalgia for the future is a gift that humans need to keep going through difficult times.

That said, more often than not nostalgia for the future steals joy from the present moment. And so, I’ve made it a habit to pass longings and daydreams through a filter to see how nostalgic they are. If I might be taking a loan against them to escape reality, I instead root myself in the joys and sufferings of the present.

Like alcohol, nostalgia has its time and place. That said, everything in moderation.

The here and now is much more wonderful and real than the once upon a time.

Relish in it so that you might truly live and feel, not merely breathe and imagine.